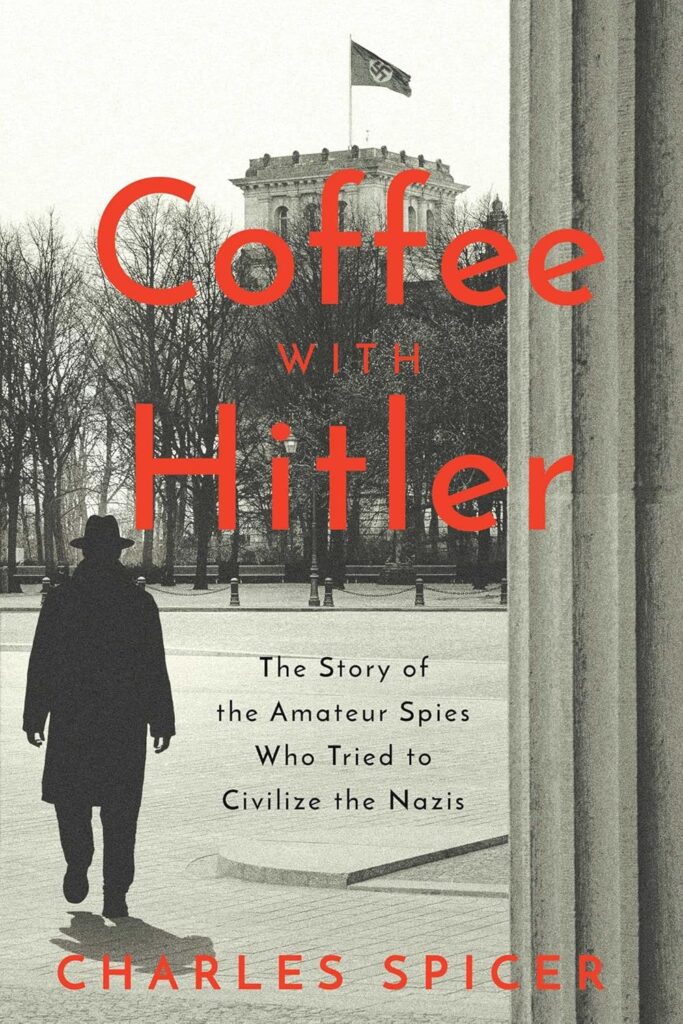

Coffee With Hitler

I’m writing this on a day when the word “appeasement” will be bandied about in terms of Trump and Putin and the Ukraine. By coincidence I just finished reading Charles Spicer’s COFFEE WITH HITLER about the informal diplomats who tried to “civilize” the Nazis by befriending them before World War II.

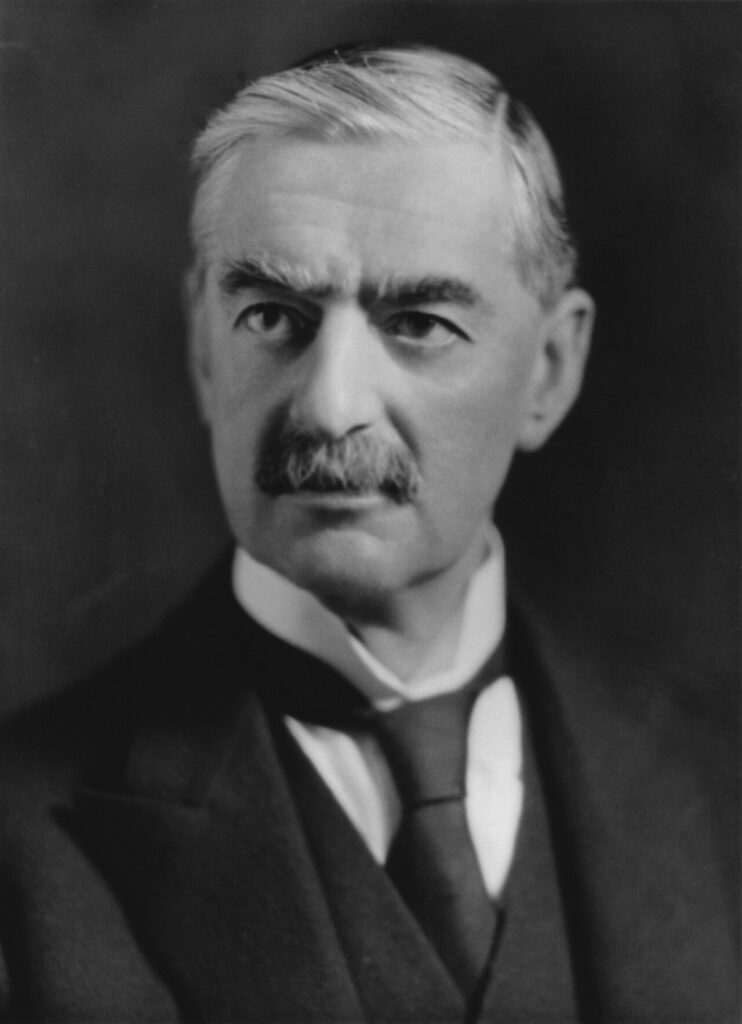

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain has gone down in history as being the biggest appeaser ever. He went to Munich at a critical moment, met Hitler, and sold out the West.

Entire books have been written about this. I don’t think it’s necessary to go into detail here, other than to say that Chamberlain thought he had good reasons to eat Nazi bullshit. But the truth is, he didn’t, not really, and was a fool. Millions died because of his appeasement – “giving in in an almost erotic way” is what political appeasement means.

Who is to say that Donald Trump isn’t almost sexually titilliated by Vladimir Putin, today’s war criminal?

But well before Chamberlain, there were informal British diplomatic maneuvers to befriend the Nazi regime, to form bonds of understanding between the German people and the British, and to “civilize” the German elite into the ways of the British Empire and the West in general. To “have coffee” with them is to “have tea” with them is to “shoot grouse” with them is to “have sticky sweet buns” with them. And concerts. And many long talks and walks, in England and Germany both.

This book is great, because it’s kind of a new topic on an overwritten war – about the unsung heroes and boobs who misstepped, misinterpreted, failed to take notes, lost their notes, fed their notes to their dogs, hid their notes, overstepped boundaries, did things they shouldn’t and should have, and so on.

And they have been, until now, a mostly forgotten crew, because formal, state-appointed diplomats and spies get all the publicity and history books. Yet in this case, some of the figures had more inside info than British formal agents had. And more social insight. They read German public opinion better. Sometimes.

Yet history has seen them mostly as appeasers of the Nazis, as idealistic folks run amuck, as idealists often are.

I’d give you names here, but I guarantee you wouldn’t know any of them. As it became clear that their efforts and info would not civilize anybody, and as war loomed, many of these figures – corporate leaders, independently wealthy artists, landed gentry, scholars – bounced into a vehement anti-German mode.

By then, what little the greater British public knew about their prior activities had stuck. They were roundly thought to be Nazi sympathizers even after they were hit by reality. Most faded from view, hid quietly in the countryside, worked at small projects.

It felt safest to downplay their past, no matter how well-intentioned. And most had been well-intentioned.

World War II popped up seemingly overnight, although it certainly didn’t. The signs were there a decade earlier. Some tried to prevent it by befriending the other side, some – the formal state diplomats – by ignoring the signs and the info from the informal eyes and ears, some by freezing in place and hoping for the best.

And some, like Chamberlain, didn’t ignore the signs. He was simply naive.

A fool on a hill?