Col. Klink’s More Famous Father

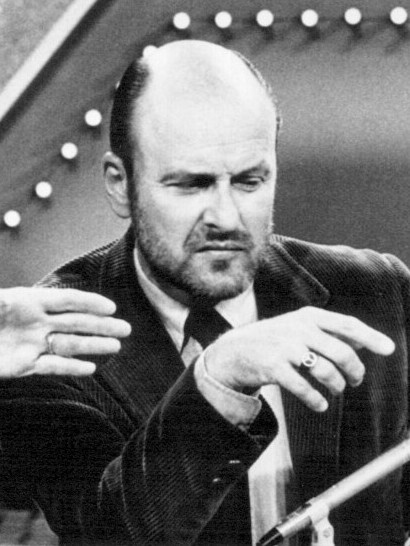

I remember how surprised I was as a kid to find out that Werner Klemperer – Col. Klink on TV’s Hogan’s Heroes – had a father who was more famous than he was.

(Notice the massive baton Klink is wielding. Some things run in families.)

I tried to resist the urge to mention actor Werner, but it was useless. Hogan’s Heroes was a program with an impossible premise – a comedy about prisoner of war camps, World War II, and Nazis – that it pulled off exquisitely.

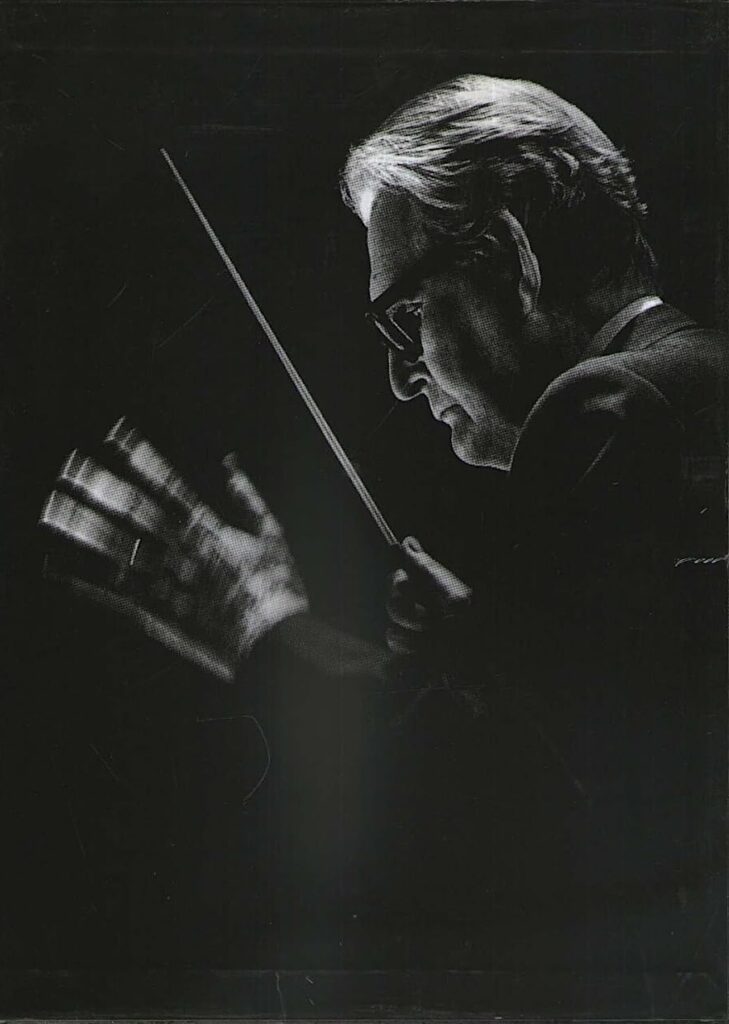

Otto’s life was also brilliant, but erratic and much, much more difficult.

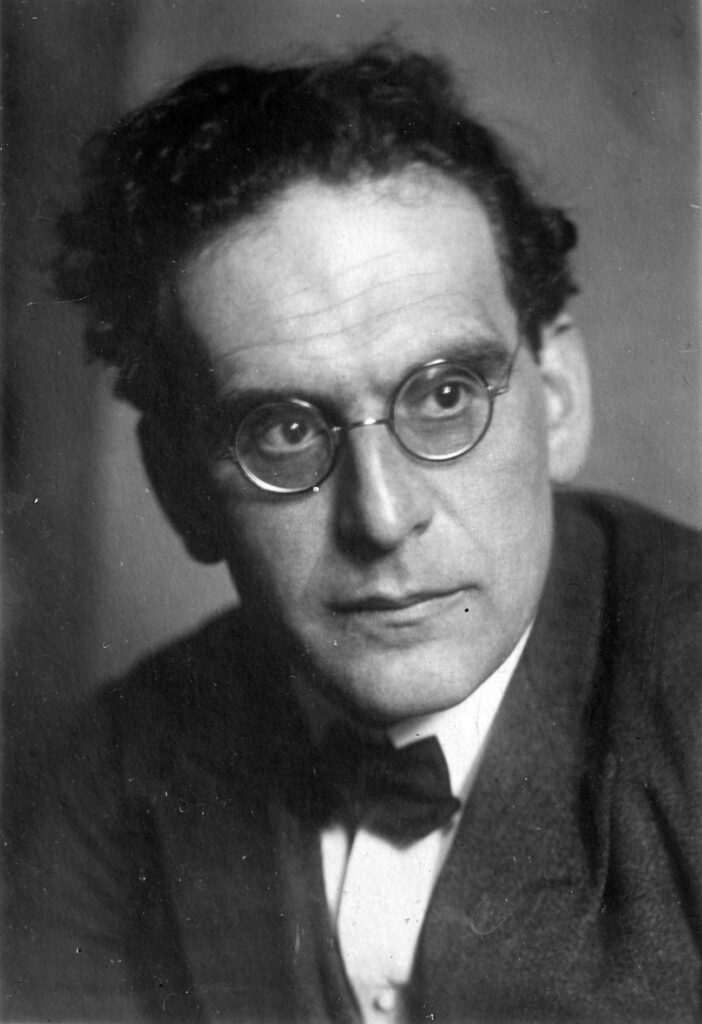

Klemperer was a direct line to the great 19th Century German conductors such as Mahler. His breakthrough came as director of the Kroll Opera House in Germany, which performed mostly avant-garde music in the early 1930’s, composers such as Hindemith and Stravinsky.

Then, in 1933, Otto fell backwards off a podium and suffered a brain injury. Always a manic-depressive, what we now call bipolar, the accident made things worse.

The manic stages lasted longer, usually for years at a time. Then came prolonged depressive periods of years duration. Throughout it all, the one constant, when not literally laid up from physical mishaps, was his conducting. Sometimes it suffered, sometimes it was transcendent.

But it was always difficult.

In 1939, he was operated on for a large, non-malignant brain tumor. I’ve never been able to find out if the growth may have been a result of his fall off the podium.

In any case, though ostensibly cured, he became mentally more unstable, became even more accident prone, had to escape Nazi Germany (he was Jewish, then Catholic, then Jewish again – his religious life was as interesting as his music and his psyche), had an unfulfilling period in the United States (which he loathed as barbaric and money-grubbing), fell into disfavor politically in the McCarthy era (he was a leftist suspected of Communist sympathies), set himself on fire while smoking in bed and made it worse by dousing the flames with camphor oil, breaking bones, and on and on.

His life was, in essence, a long run-on sentence. One in which he heroically endured.

And then he blossomed in his old age. He discovered the joys of the recording studio.

He conducted and recorded almost until his death at 88 in 1973.

He dragged a 19th Century monolithic, monumental conducting style into the mid-late 20th Century. He was a giant of a man physically and temperamentally, fearsome to musicians but also respected. His sense of humor was sharp, too.

That’s where Werner got his skills.