The Fabulous Phonograph

You can’t kill music in your home, although many have tried to beat it to death.

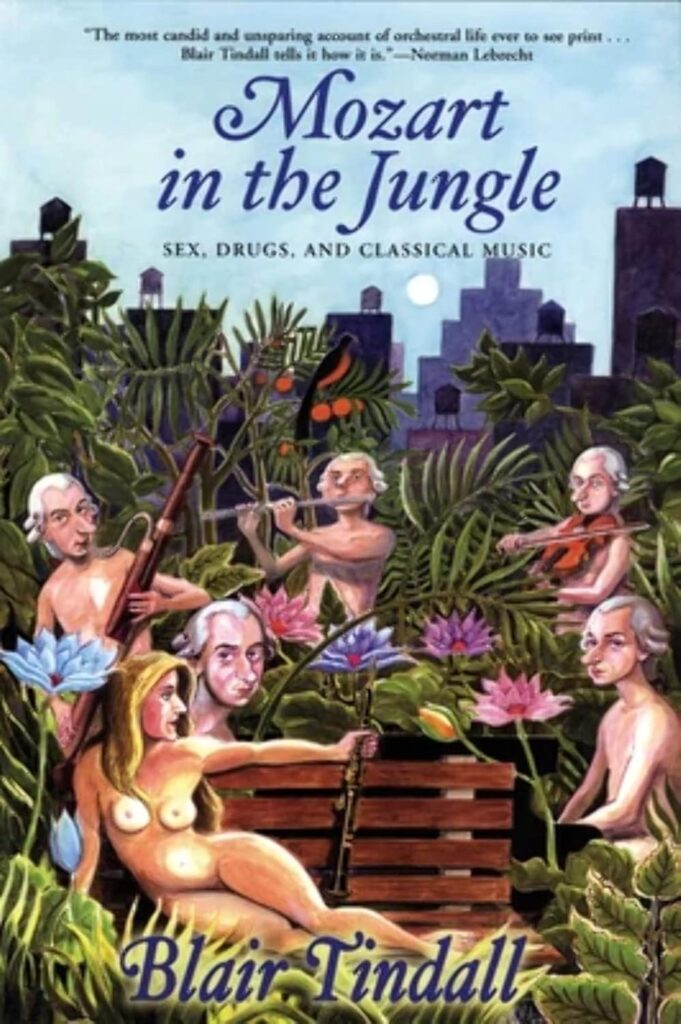

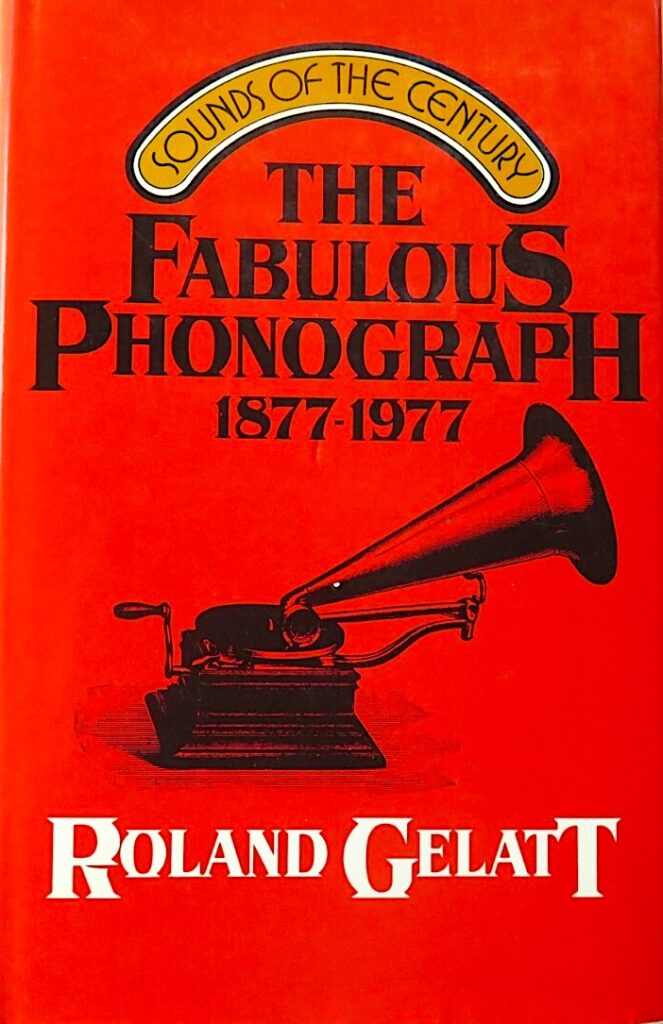

Roland Gelatt’s epic THE FABULOUS PHONOGRAPH 1877-1977 ends its story in 1977 because that’s when this now-rare book was published in its second edition.

It’s a shame that it ends when it does because 1977 is about when digital music and MTV and eventually streaming started, and before long, vinyl made a startling comeback. Now, in 2025, there are even signs that CD’s are making their own comeback.

And, of course, tubes have long been “back” among the most serious – or most deranged – audiophiles.

Why tubes now? Because like vinyl, they sound better than sterile 1’s and 0’s.

But believe me, the history of home audio is already dense enough without adding its most recent, and volatile, years.

You would only read this book if you were a nut, provided you could source it from interlibrary loan or a used book store. Because it is suffocatingly, if entertainingly, detailed.

I am so sick of tracing the path from gramophone to Edison cylinder to shellac to Nazi German magnetic tape and tape recorders to zonophones to record players to stereo to headphones to cassettes (also making a mild comeback today!). I am sick of following the massive and ridiculous trade wars and obscure dead artists and the fall and the rise and the even more advanced fall of recorded classical music.

This is a reference book, a textbook, and very much the sort of excellent writing we had before about 1990, scholarly yet accessible to almost-normal people.

There have been many calls to revise THE FABULOUS PHONOGRAPH, but I think it’s too late. Nobody writes this well now. The two styles of writing would mix like water and oil. Or like digital and analog.

But I did learn about Nipper, the little dog in the painting and ad logo, HIS MASTER’S VOICE.

Why was the dog named “Nipper”? Because he was a nasty little S.O.B. who would nip at the heels of household visitors.

His burial site was under a mulberry tree in Kingston-On-Thames, and it was honored with a plaque in 1949. A plaque on a bank that replaced the mulberry now honors Nipper, the little bastard.

And so the record goes round and round . . .